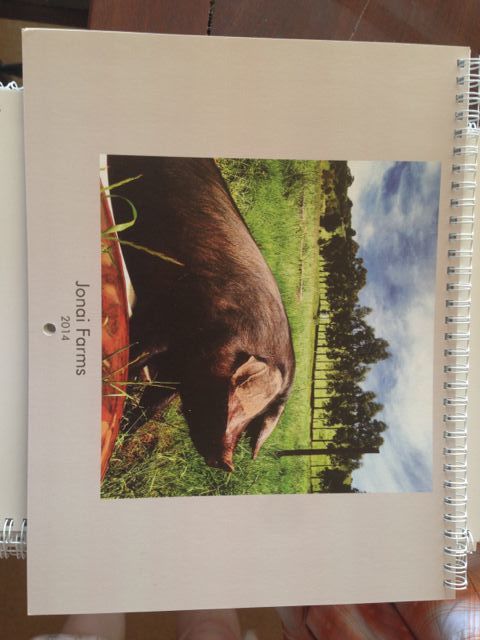

Welcome to the second instalment of Grow Your Ethics – supply chain control and connectedness. In Part One I shared what led us to grow our ethics and detailed our farming system out on the paddocks. In this post I’ll outline the rationale for a short supply chain and direct sales and then show you what a typical fortnight looks like when you grow, butcher and deliver all your own meat.

In modern conventional livestock farming, you raise the animals (pigs and poultry typically in sheds), and then take or ship them to the saleyards and hope for a decent price. That price is subject to market fluctuations based on whether there’s an over or under supply of animals and feed, and what processors and retailers are willing to pay to maintain their own share of the profit.

In Australia, pig carcasses are selling for between $3 and $4 per kilo at the saleyards. Let me take you through our input costs to see what that would mean for a farm like ours…

We’ve managed to get our feed costs down to below $125 per grower (from $200 when they were on a diet entirely of custom-made commercial pig). That $125 includes the small ration of commercial grain and the motor vehicle costs of collecting the spent brewers’ grain and milk from other food waste streams.

Based on saleyard prices, on a 55kg carcass, we might get $200. By the time you’ve accounted for labour, transport and general farm costs on top of feed, it’s really hard to make a living in that system. Of course you then understand the pathway into intensive industrial agriculture to achieve ‘economies of scale’ at the expense of animal welfare.

So the obvious thing to do for a small farm like ours is to sell directly to eaters, but of course there’s still processing that must happen first. Abattoir costs in our region are cheap – just $37 per pig at ours. But butchering costs are not cheap – we were paying an average of $200 per carcass before we built our boning room on the farm.

These financial realities, along with issues of reliability and the desire to work closely with our produce all the way to the eater are what led us to take on the butchering of all our meat. And what it’s meant to us goes far beyond control and profitability – it has deepened our knowledge of the animals out on the paddock because we understand what those working muscles end up like in the boning room. That in turn has extended my knowledge of the best ways to cut and cook different muscles. The butchery has also strengthened our relationships with our community of eaters as we discuss everything about the pork and beef they buy from us quite literally from paddock to plate, right down to the herbs I pluck out of the garden and use in our single-estate sausages.

Last year we introduced our community-supported agriculture (CSA) model as well, which now has over 50 members. The CSA reduces my admin and logistics load and provides us with a known base income for the year, and develops even stronger relationships with our regular community of members. We love the feedback we get from our community – positive and critical – and they help spread the word about respecting the pigness of the pig.

When we took over the butchery side of the business, I gained a much greater understanding of the actual labour input to the further processing, which has meant some changes to our pricing. I often say I’m basically a Marxist when it comes to pricing – I charge on the use value and actual input costs rather than what the market will bear.

For example, belly from us costs $26/kg and a bone-in shoulder is $25/kg as the butchering is quick and simple for those cuts. A boned-out coppa roast (aka neck or scotch) is $30/kg, and bacon is $32/kg for a slab or $36/kg for sliced – slicing is very labour intensive!

If you’re a chef, you’ll pay the same as everyone else. Our prices are based on what we need to charge to make a living, and dropping those prices would render us unviable. But we recommend that chefs buy whole or half beasts at $16/kg, or whole primals (shoulder/barrel) at $20/kg. See how it works? The less work we do, the less you pay.

I’ve added a Cook Your Ethics workshop to our repertoire to teach chefs how to butcher whole carcasses, which is intended to help chefs choose free range by buying half or whole pigs as per the pricing above. We hope this enables more restaurants to choose genuine free-range pork. (And in case you’ve missed the confusion around ‘bred free range’ v. genuine free range, I’ve written about it over on my food ethics blog.)

Logistically, what happens when the carcasses come back to us from the abattoir is this…

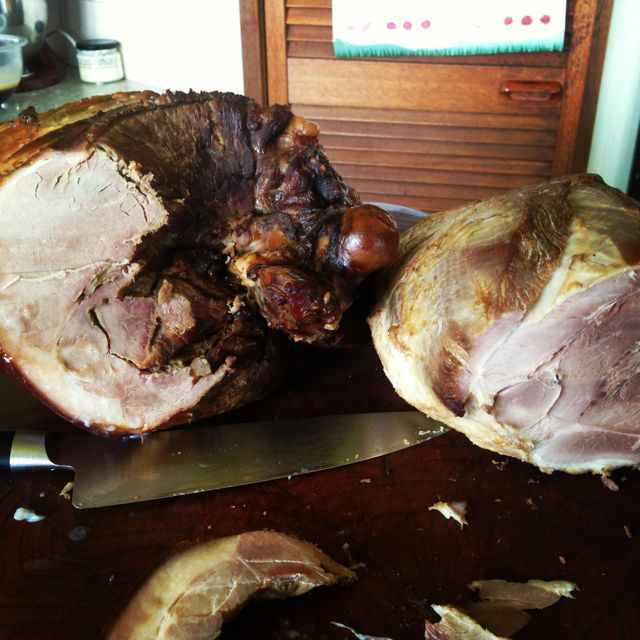

Eight pigs per fortnight are sent off and one steer per month. The pigs typically go to the abattoir on a Thursday and are back into our chiller on Friday. I pull the bellies off that afternoon and get them into salt for bacon.

On Monday following, we (my Head Meat Grrl Jass, and our wonderful residents – currently Andrew and Theresa, and I) break down the shoulders and barrels into a set repertoire of cuts plus any custom orders.

Tuesday morning we bone out the back legs for schnitzel, porko buco and our single-muscle hams (I do a brined & smoked noix de jambon), and the rest goes to sausage. Tuesday afternoon we make 40-60 kg of sausages, flavour dependent on the season (Mexican chorizo, Toulouse, sage & pepper, apple & sage, bratwurst…).

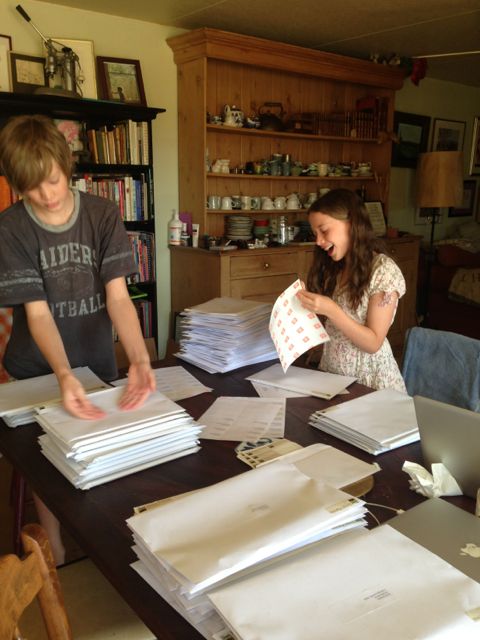

Wednesday morning we slice and pack bacon, wrap hams, then sanitise the benches and pack sausages. That afternoon we pack orders – somewhere between 200 and 350kg of meat depending on whether it’s a regional or metropolitan fortnight. I send invoices that night after recording all the weights during packing.

Thursday morning I load up the coolbox on the back of the ute and head off on deliveries – nine hubs around Melbourne one fortnight and five in the region the other.

Friday I catch up on farm accounts and admin, and the following week I call my ‘non-cutting week’ even though we break down a side of beef on Thursday and pull those bellies off the next lot of pigs on the Friday… repeat ad infinitum. But the fortnightly schedule is amazing – it gives me the freedom for the writing and fair food advocacy work I do, now in my role as President of the Australian Food Sovereignty Alliance (AFSA).

So for those who’ve emailed me during a cutting week, I hope this explains my silence. And for those who’ve emailed me in a ‘non-cutting week’, I hope this explains my slowness. J

Stuart has completed construction on the commercial kitchen and curing room and we’re looking forward to having the facility inspected by Primesafe in a week’s time. My fortnight will get a bit fuller with that addition as we transform every bit of the beasts into delicious nose-to-tail offerings such as bone stocks, pate de tete, lard, fricandeaux, and a range of single-muscle cures such as jamon, coppa, and guanciale. We’ll be submitting our process to the regulator to make farmstead salami within the next couple months as well, so watch this space!

Supply chain control and direct sales make us viable, deeply, viscerally happy, and connected to our land, our animals, and our community. We are fully accountable for every step except slaughter, and we’re working with others in the region to hopefully solve that problem.

In the next instalment of Grow Your Ethics, I’ll share how and why we avoid a growth and competitive mentality, how we manage the farm with fair labour, what radical transparency has meant to us over these past few years, and how all of these parts of our system come together to nourish us and our community while still respecting the pigness of the pig.

From February onwards, Sal let me cut with him each fortnight when we sent him our pigs, which was incredibly generous considering I slowed him down to about quarter speed. He was a good-humoured taskmaster, teaching me how to cut my bellies straight, where to find the joint on the shoulder, and to waste nothing, as well as how to stop waving my boning knife around in a rather alarming fashion. He makes quality sausages too, which were certainly well received by our earliest Jonai Farms community of eaters!

From February onwards, Sal let me cut with him each fortnight when we sent him our pigs, which was incredibly generous considering I slowed him down to about quarter speed. He was a good-humoured taskmaster, teaching me how to cut my bellies straight, where to find the joint on the shoulder, and to waste nothing, as well as how to stop waving my boning knife around in a rather alarming fashion. He makes quality sausages too, which were certainly well received by our earliest Jonai Farms community of eaters!